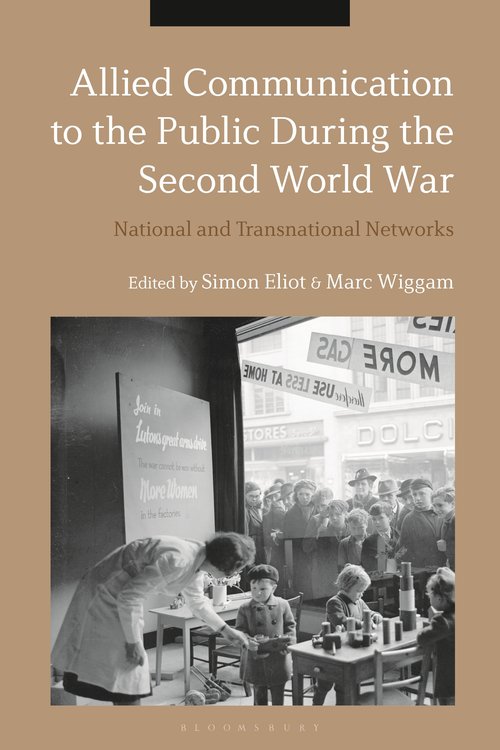

Allied Communication to the Public During the Second World War

One of the main conclusions of our project is that the Second

World War was fought with information as well as weapons.

One of the main conclusions of our project is that the Second

World War was fought with information as well as weapons.

The Ministry of Information is an obvious example of this trend. It represented an attempt by the British government to use communication to win and hold the trust of domestic and international audiences.

Britain – like all the Allies – had to develop new ways of communicating with its citizens, and to civilians in neutral, occupied, and enemy countries. Film, radio, photojournalism, comics, and advertising were all used in propaganda which, for the most part, had to be based on truth to be trusted by those who received it.

Different cultures had to be addressed in ways that reflected their values, and yet linked them to the aims of the war effort. Minorities had to be protected, but not made into special cases. And above all else, those communicating had to understand how their messages were received, and had quickly to change approach if the feedback proved negative.

These themes run throughout our newly-published book Allied Communication to the Public During the Second World War (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019). The book, edited by Professor Simon Eliot and Dr Marc Wiggam, brings together ground-breaking research on how information was used, distributed, and received during the war.

Adopting a transnational approach, the chapters range from discussions of the National Savings Movement in the UK to the challenges faced by BBC broadcasters in India during the war. There are chapters on the Ministry of Information, the Army Bureau of Current Affairs, the BBC German Service, the making of films promoting racial equality by the USA’s Office of War Information, the resistance to political censorship by Allied journalists, propaganda in Arabic-speaking regions, and the problems of making the Allied case in Spain and Portugal.

The book expands on papers delivered at our 2017 conference on ‘Information and its Communication in Wartime’ and we are delighted that it includes chapters from Christopher Bannister and Henry Irving, alongside an introduction by Simon Eliot and Marc Wiggam.